If you enjoy reading this, please click the 🖤 above and share with others.

It’s when the doctor asks me if my father might have served as a negative role model that I wonder if I’ve picked the right man for the job. Mustering phrases such as “loving and supportive parent” and “wise and caring mentor,” I prepare to deliver a forceful repudiation of his suggestion. It’s 1998, and I’m in a state of some distress, beset by a loud hissing in my ears. It’s tinnitus. That much I know. And it’s the start of an entirely new relationship—one I still have—with sound.

“No,” I reply in the end. I’m anxious to hear what the doctor has to say. Currently, no known cure for my condition exists. Yet it affects an estimated 740 million adults globally and for more than 120 million it severely impairs quality of life. Czech composer Bedrich Smetana was among them. Listen to the last movement of his string quartet From My Life to hear the piercing notes that echo the sounds he found so devastatingly disruptive.

In recent weeks, I’ve been among these sufferers—a prisoner trapped in some auditory hell. Suddenly spending the night at home alone is torture. But in the company of friends, I lose track of the conversation and sink into the miserable company of this unwelcome presence. The sound is like high-pressure steam escaping from a pinhole in a pipe. At night it’s unbearable. I feel that life as I knew it has ended.

But now, I’m in the Devonshire Place practice of otologist Jonathan Hazell, and what he has to say is intriguing. It transpires that Hazell (he’s now retired) is one of the world’s leading experts on tinnitus, working closely with Pawel Jastreboff, his US counterpart.

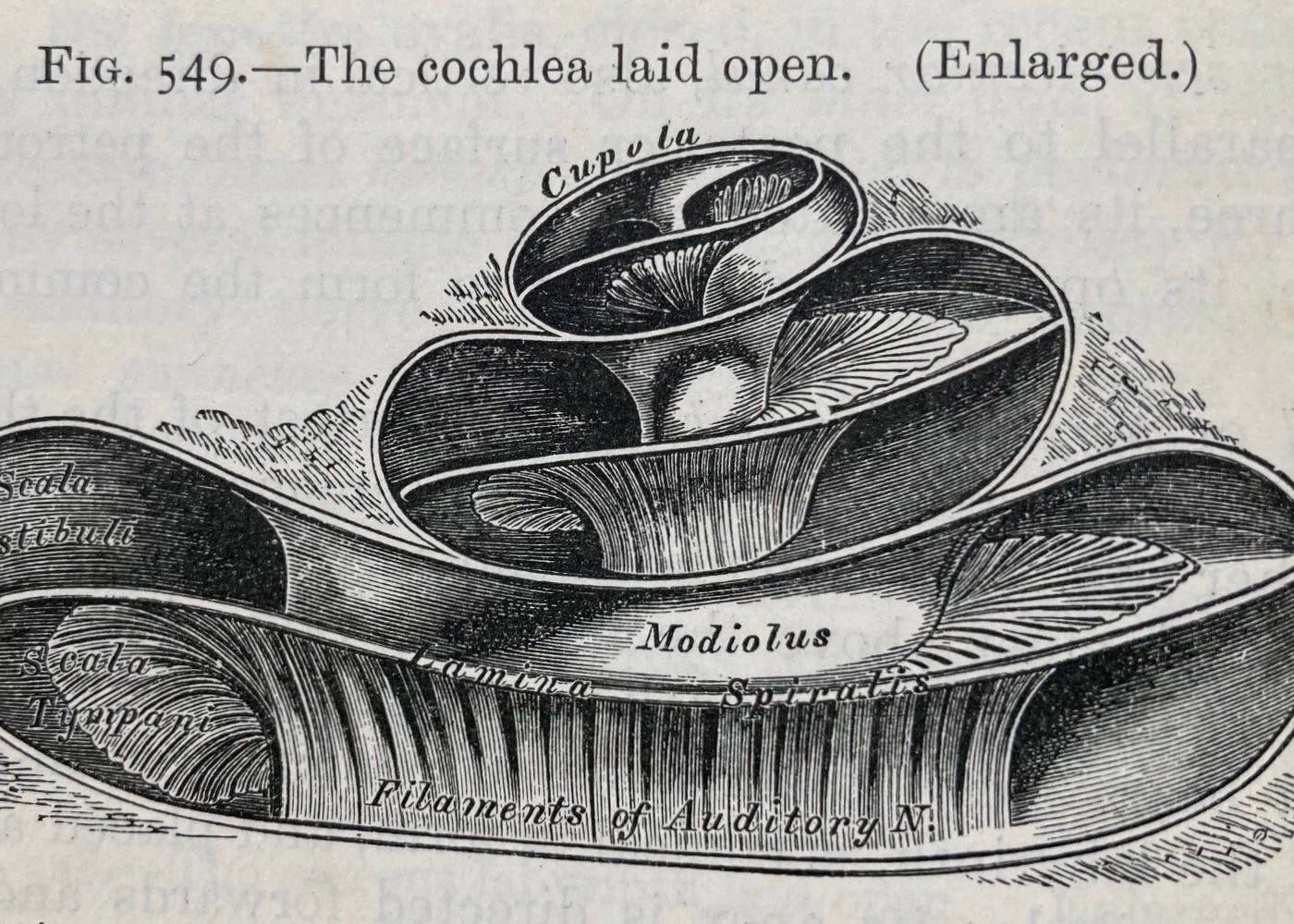

He certainly seems fully immersed in the auditory world. A silver frame on his desk contains, not the smiling image of his wife or snapshot of his children, but a black-and-white photograph, enlarged many times, of what I presume are the hair cells of the inner ear.

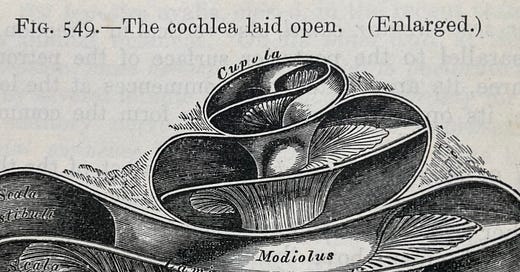

The other accessory on his desk is a cassette recorder. Hazell is taping the session. As he races through the workings of the cochlea and the purpose of those hair cells, I begin to wish I’d paid more attention during biology classes and worry that in our next lesson—sorry, consultation—I may be tested on the information he’s now imparting. No, he explains, the recording is for me to play at home.

So here’s the bit that interests me. Hearing, he says, is a complex learning process that begins in infancy, when the brain continuously matches memory patterns with those coming from the ear. Thus sound is never free from meaning. Take a cocktail party. Surrounded by noise, you hear the chatter without recognizing individual words. If your name is pronounced, however, it leaps out at you like a siren, even if uttered softly. Similarly, a mother wakes to the sound of her baby crying, even though she’s just slept through a thunderstorm.

For Hazell and Jastreboff, this auditory memory is crucial to understanding tinnitus. It shapes our emotional responses to sound. It’s why reactions to tinnitus vary. Many experience only mild annoyance while for others, it’s extremely distressing.

This, he explains, is where my father comes in. I had told him my father had tinnitus and found it deeply disruptive. On hearing the same sound, I had clearly panicked. In other words, knowledge had shaped my perception of the noise.

“You need to make friends with it,” Hazell tells me. At first, this makes me want to laugh. Sitting opposite this medical professional in a smart suit, with a posh accent and an office in London’s distinguished Harley Street district, this touchy-feely piece of advice seems highly out of place. But as soon as he starts explaining it, I understand.

Rather than trying to remove the sound (which for now seems impossible), Hazell and Jastreboff’s retraining therapy focuses on perceptions of tinnitus and helps patients treat it like a neutral presence. As part of their treatment plan, you lie on the floor and actively but calmly listen to the sound, stopping as soon as distress kicks in. Every day, you try to extend that period.

This has me wondering—can we change the way we experience other things by thinking about them differently?

The idea takes me back to a trip I made in 1989 through the mountains of northern Pakistan. After a week enthralled by its spectacular collision of vast tectonic plates but exhausted by the bitter winter wind, I found myself wandering through a local market seeking warmth and sustenance. At one stall, a man in a shalwar kameez stood behind a vast aluminum pot heated by an open flame. He was stirring what it contained and occasionally, by spooning it high into the air with a large ladle, creating impressive cascades of steaming hot liquid.

“Tea?” he offered.

I bought a cup. I took a sip. I nearly choked. The tea was laden with sugar and thickened with condensed milk, the kind that’s already been sweetened. A double hit of saccharin.

Politeness stopped me from spitting it right out again. But I was torn between my revulsion and my desperate need for nutrition. Then it occurred to me. What I was drinking was remarkably similar to hot chocolate. I took another sip. Yes, that’s it! As soon as I considered myself to be drinking hot chocolate, the vile “tea” became acceptable. By the time I finished my cup, I was rather enjoying it.

So can the same principle be applied to something like tinnitus? I’ve read that in some parts of rural India, people with the condition feel blessed because they believe the sound to be the Gods speaking to them.

I do not feel blessed. Three decades on from my session with Hazell, I still find the hissing in my ears unpleasant and annoying. However, what he told me that day has enabled me to develop a relationship with the sound that is, if not affectionate, manageable.

Moreover, the approach has helped me deal with some of life’s other annoyances. Say your neighbors start playing loud music. Your reaction varies according to whether you consider those neighbors friends or strangers (it’s one of the reasons I always try to befriend my neighbors).

Much like a noisy neighbor, the “friend” that is my tinnitus is something with which I can co-exist. It never disappears or diminishes—and yes, on occasion I do wish it would just shut up—but I spend much of my time unaware of it. And life as I knew it has certainly not ended.