Truthtellers Meet Storytellers

A set of photographs prompts an intriguing blend of fact and fiction

If you enjoy reading this, please click the 🖤 above and share with others. If you want to support my work, you might consider becoming a paid subscriber.

In a black-and-white photograph, a middle-aged woman in a hijab grins cheerfully at the man sitting next to her. They are united, not just by a smile, but also visually, in the way the intricate tattoo decorating the man’s hand echoes the patterns of the woman’s shirt. The smile speaks of a friendship between two people from very different cultures. The Sarson’s label on the vinegar bottle tells us we’re in a British pub.

What the photograph does not immediately reveal is that this is a worlds-within-worlds moment—one that prompts intriguing questions about the role of truthtellers versus that of storytellers.

It starts with a camera.

In the opening scene from The Old Oak, the 2023 film by British director Ken Loach for which this photograph was taken, white British locals from a gritty former mining town in northern England start harassing a group of Syrian refugees who, in 2016, have arrived in a bus to be resettled there.

As one of the refugees, a young Syrian woman called Yara (played by Ebla Mari), takes photographs to document her arrival, one of the locals grabs the camera—given to Yara by her father before leaving her homeland—and starts snapping. When she demands the man return it, he throws it onto the ground, shattering its lens.

Yara and her camera (it gets fixed) are at the heart of the story, much of which unfolds in The Old Oak, a rundown pub where Yara and the pub’s owner T.J. form an unlikely friendship and find a way of uniting the community through food and photographs.

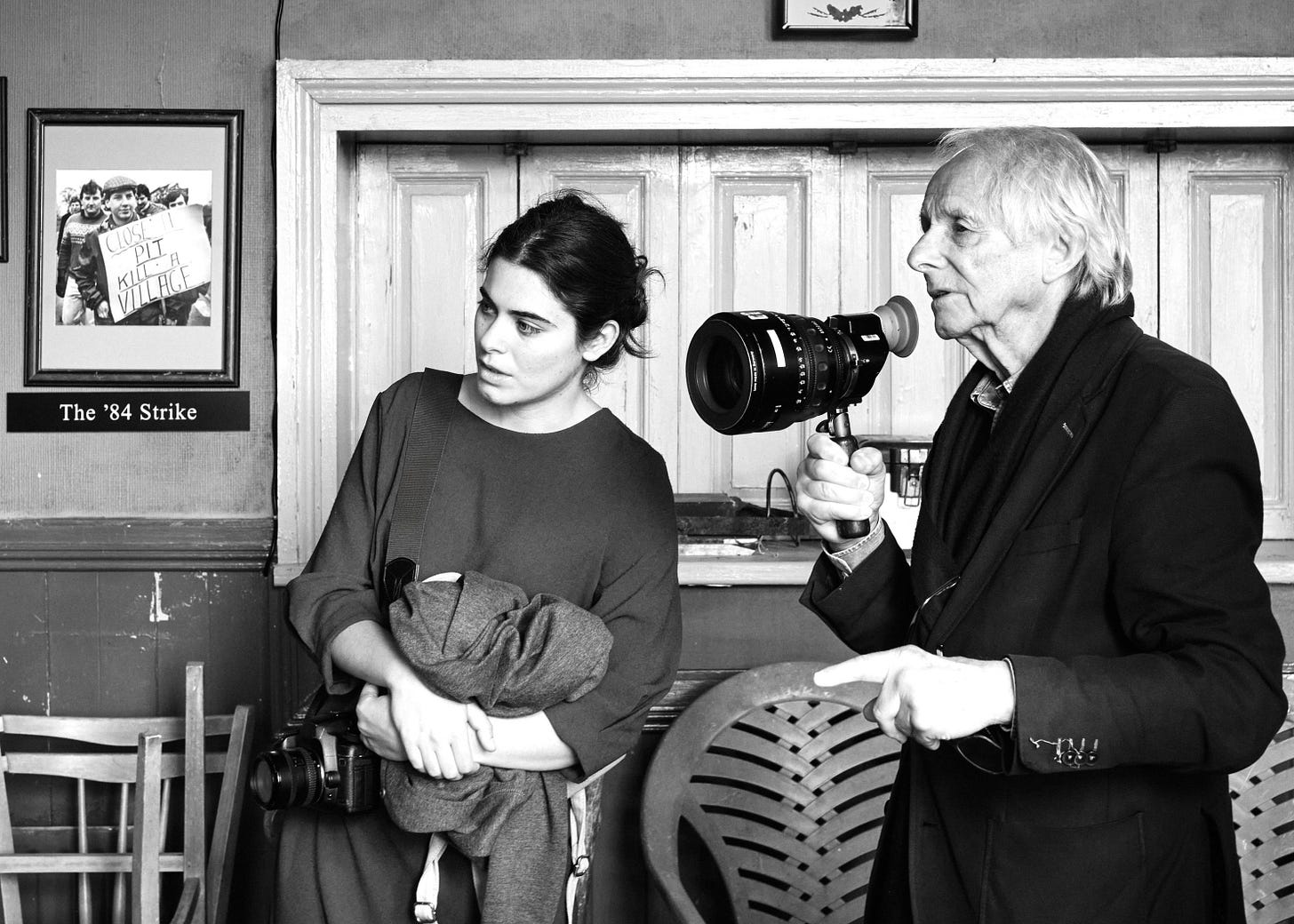

I’m standing looking at these images in an exhibition—part of the 2025 Photo|Frome festival—curated by my friend Joss Barratt a production stills photographer who has had a 30-year creative partnership with Loach.

The show features some of work he has produced for Loach’s films alongside images made by documentary photographers such as Magnum’s Susan Meiselas, known for her 1970s images of war-torn Nicaragua, and British social realist photographers Nick Hedges and Tish Murtha.

There’s something slightly unsettling about the combination of images capturing the grim reality of poverty and deprivation and the polished color marketing photographs from the world of cinema. For most people, that’s precisely what makes the show so compelling.

I agree. But for me, it’s one set of black-and-white photographs that I find most fascinating. Because these are images that, in unexpected ways, blur the boundaries between fact and fiction.

It’s complicated.

Not only did Joss take the movie stills—photographs that capture a flavor of a film for its marketing campaigns—he also shot those black-and-whites. They’re the images supposedly taken by Yara in the story.

In a clever bit of cinematic gymnastics, these images are all we see in the film’s opening moments as the soundtrack captures the hostile comments of the locals and the clicking of Yara’s camera.

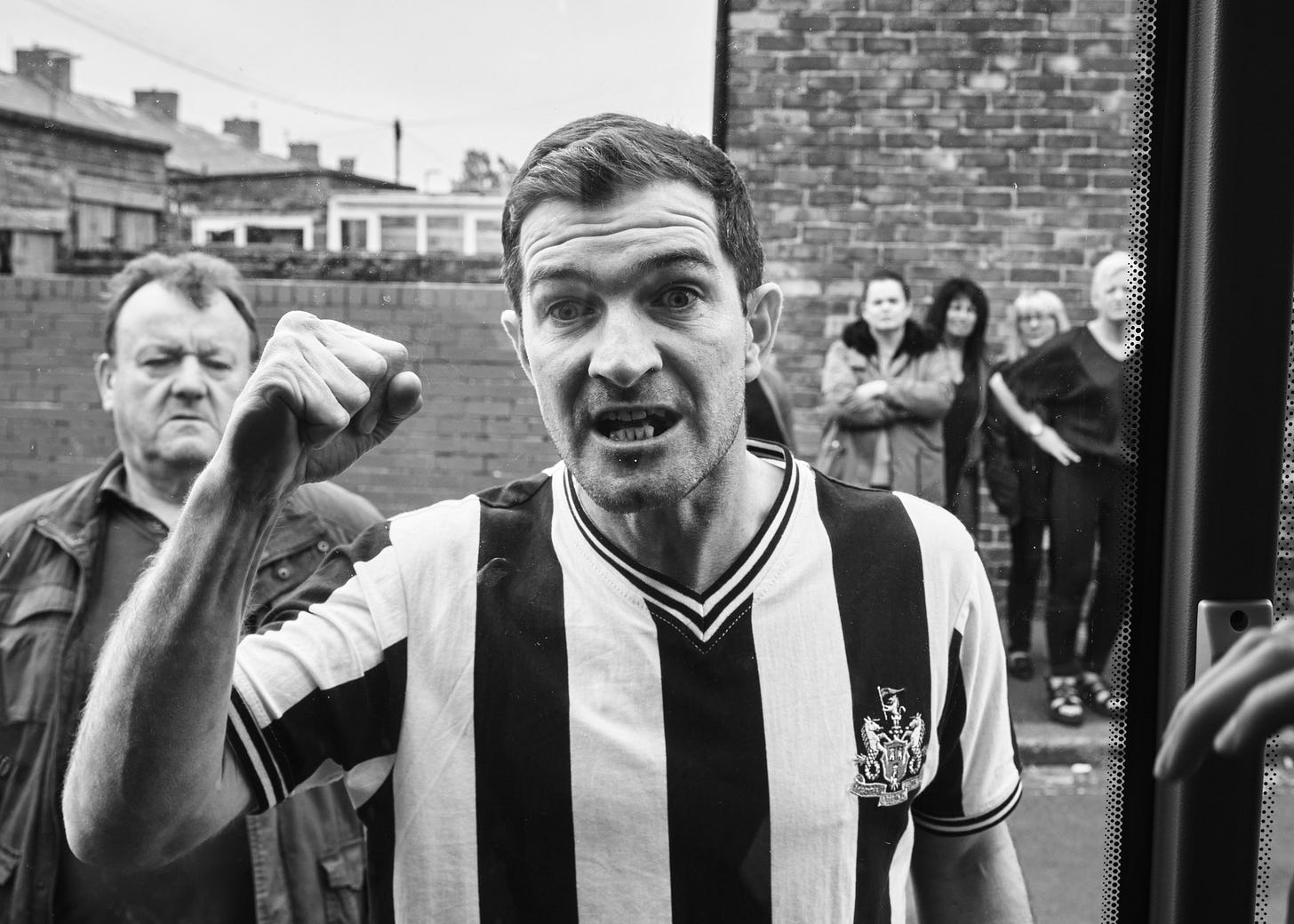

One man, the chief rabblerouser, comes to dominate the shots.

With no break in the soundtrack, he approaches the bus door and is suddenly transformed from a motionless black-and-white figure, fist in the air, into a live person, bristling with anger and resentment.

We see more of Yara’s photographs towards the end of the film, when the locals and Syrians gather for a feast in the pub followed by a slide show in which, to laughter and gasps of delight, she shows them the images she’s taken since arriving.

In reality, these are Joss’s photographs. And Joss himself had to do a bit of role playing to make them. As he created the portraits and street scenes that would appear in the film, he had to look through the eyes of young woman navigating a strange place far from home and imagine what she would have seen—and been drawn to photograph.

He also worked with Ebla as she prepared for her acting role in the film, walking the streets with her in search of real subjects to document. “I was keen that she held the camera property and that it looked natural to her,” he says.

The blurring of truth and fiction doesn’t end there.

“I did a sort of hybrid,” Joss tells me. “We had extras, we had the main actors, we had supporting actors and I took them into the streets we were filming in.” In what he describes as a constructed reality, Joss would wait for a real resident to pass before taking the shot. “I was making the accident happen,” he explains.

Of course, what made possible Joss’s constructed reality was Loach’s approach to filmmaking. “Because the films are completely immersed in the landscape and geography they’re talking about, you can take a character round the corner and put them against a brick wall and it still belongs to that world,” he explains.

As I stand looking at these photographs, my head is spinning.

They represent an imaginary woman called Yara, an actor called Elba Mari, who lives in the Golan Heights, on the border between Syria and Israel, a cast of characters played by both professional and non-professional actors and a British production stills photographer called Joss Barratt who, following a story created by Paul Laverty, Ken Loach's longtime screenwriter, and inspired by the documentary images of Nick Hedges and Tish Murtha, has captured the essence of a northern British town as it might have been seen through the eyes of a Syrian refugee.

As I said, it’s complicated. But as Loach likes to put it, the question to ask is not, “Is it telling the truth?” but “What truth is it telling?”

2025 Photo|Frome, Frome, Somerset, UK—April 5 to 27