When Hairwork is Hard Work

A lockdown practicum offers insights on our enduring connection with the dead

If you enjoy reading this, please click the 🖤 above and share with others. If you want to support my work, you might consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Whenever an email from Morbid Anatomy pops into my inbox, I’m always pleased to receive it. This quirky institution explores the intersection of art, medicine, death and culture through books, online content, exhibitions and intriguing workshops (one of the most popular is its taxidermy class).

I love what they do so I’m on the mailing list. And its latest missive has plenty to attract the curious.

Among the offerings are three online courses, one on how relics connect the living and the dead, the other on the history of fairies. Both sound appealing. But the third—a four-week class on Victorian hairwork that’s part history, part practice—prompts a memory. Because five years ago, I took a much shorter, online version of this same course.

So what is Victorian hairwork? The practice emerged when, following the death of Prince Albert in 1861, Queen Victoria turned grieving into an art. The inconsolable widow wore nothing but black and, in addition to her inky attire, expressed her perpetual sorrow through lockets and other pieces of jewelry in which she kept curls of her husband’s hair.

Hairwork took off. Mourning lockets were soon being mass-produced. Behind glass or crystal in pendants, brooches and necklaces, hair was crafted into intricate designs using crosshatching, weaving, plaiting, feathering and curling.

For me, this is familiar territory. For my book, Making an Exit, I travelled around the world and back in time looking at the different ways in which we send off our dead and establish enduring connections with their remains. So when, in 2020, Morbid Anatomy’s June newsletter announces an upcoming Victorian hairwork class led by master jeweler and art historian Karen Bachmann, I sign up immediately.

The first task is assembling the materials: a spool of 26-gauge copper wire, one knitting needle, a roll of masking tape, a skein of black embroidery floss or some narrow ribbon and—the essential material—horse or human hair. Soon, I’m sourcing all this online. But I hesitate before choosing human hair. The idea of manipulating stuff from another person’s head seems, well, a bit creepy.

I’m reminded of “Shag” an unsettling artwork in which Bharti Parmar has created a rug entirely out of human hair. “‘Shag’ is a complex work which attracts and repels in equal measure,” the UK-based artist explains in an interview. Acknowledging her debt to Surrealism but also her interest in Victorian hairwork, Parmar argues that what makes hair compelling as a creative material is its “curious paradox.” It is both dead and (she quotes psychologist Charles Berg) “the vital surrogate of the living person.”

I like this analysis but I’d rather not tangle with human hair right now. So I text my friend Jasper Winn, a travel writer, expert in horsemanship and someone who is not easily fazed. He is intrigued and kindly agrees to mail me some black horsehair.

The next day, on a country walk (I’m in the UK, in my house in a small rural town), I spot something dangling from a fence that looks like a clump of dark brown horse’s hair. It is. As to how it got there, I’ve no idea. Never mind. Quickly, I shove it into my bag in case someone sees me and thinks I’m completely mad.

Of course, at any other time I’d have walked straight past this piece of equine detritus. But with the workshop looming, hair is on my mind. It’s rather like that stage of home renovation when you need to choose the door handles. Suddenly everywhere you look, there are nothing but door handles.

Back home, things get weirder. As I wash the “horsehair,” I find it’s actually blond and I’m now pretty sure it’s from a cow’s tail. It had looked dark brown because it was caked in dung. It’s also extremely wiry so, having cleaned it, I reach for my (very expensive) conditioner and start massaging gobs of it into the hair to try to soften it up.

OK, so I know we all did unusual things during the pandemic, but this surely ranks as one of my most bizarre lockdown activities.

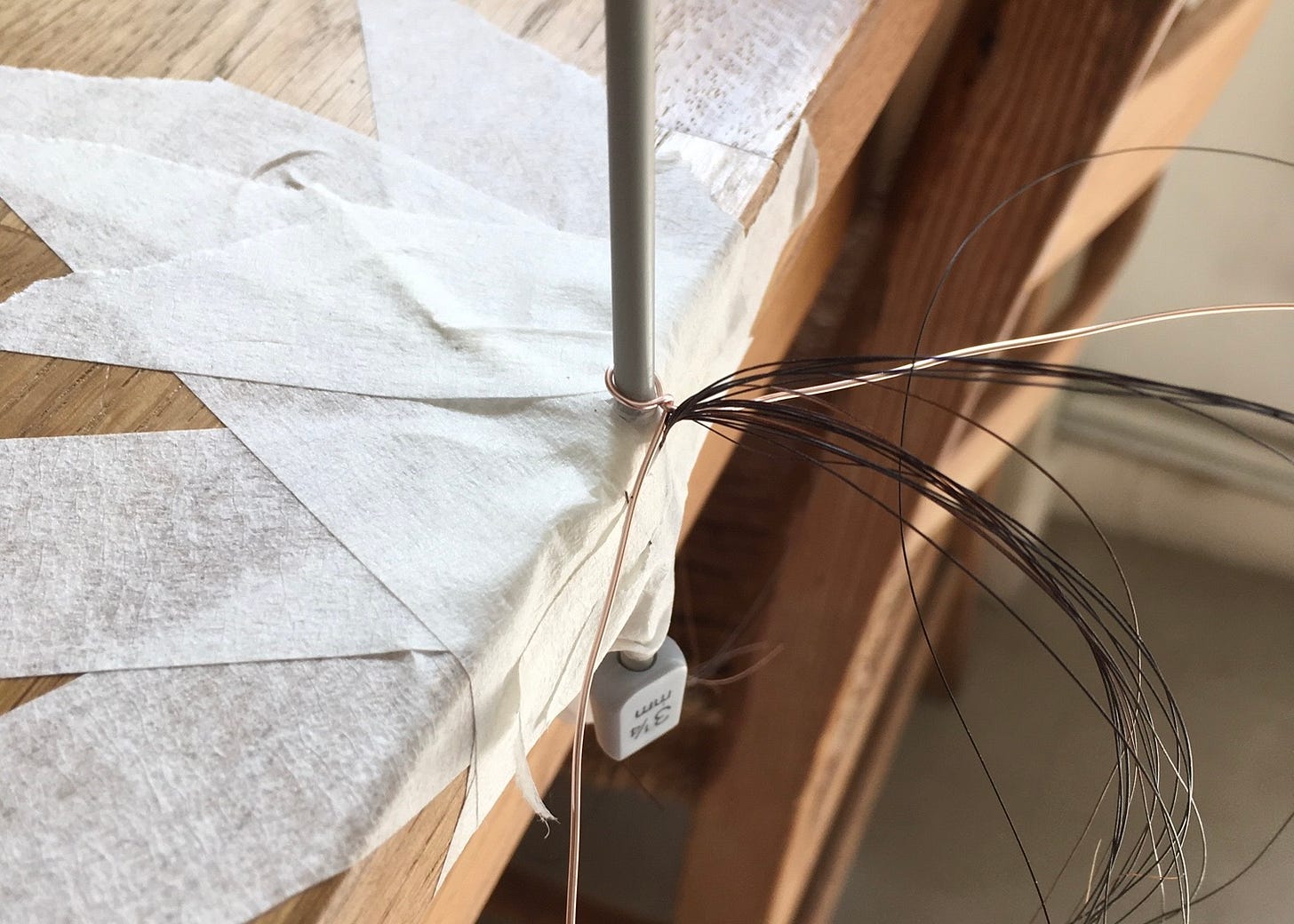

The fun continues during the workshop. After taking us through some fascinating hairwork history, Bachmann gets us going on the practical side of the course. Before too long, I’m using the masking tape to strap the knitting needle and two strands of the copper wire to the edge of my kitchen table.

“This is the part where you’re gonna be, like—how the hell did people do this with only two hands?” says Bachmann.

No kidding. I’d say you’d need at least four. That’s because you have to take a bundle of hair, tape one end of it to the base of the knitting needle and create loops—the bows or petals of the design—by wrapping the hair around the needle and then crossing the copper wires over each other to secure the hair loops.

Lost? I certainly am.

“Now, listen up everybody.” Bachmann does not mince her words. “You can wrap to the right or wrap the left—I don’t care. But damn! Be consistent. Don’t start wrapping this way and then start wrapping that way because the loops will come undone. They will.”

We have been warned.

I manage to follow Bachmann’s instructions—just about. I still can’t see how my clumsy attempt to create loops can result in anything resembling the intricate hairwork patterns in the photos she showed us earlier.

But as Bachmann might have put it—damn! When I pull my washed and conditioned cow’s hair off the knitting needle, I appear to have created a loop. I repeat the process, creating two black loops from the horsehair Jasper sent me, and one more from my blond cow’s hair. Tied together with a ribbon, they make what looks vaguely (OK, very vaguely) like a tiny bouquet.

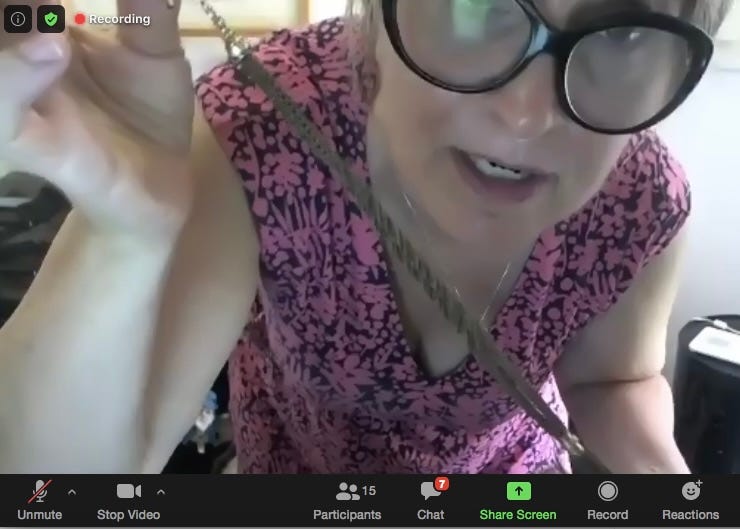

As we hold up our hairwork to our cameras, I’m feeling good, partly because Bachmann tells me I’m her first student to show up with cow’s hair but mainly because I have tackled something seemingly impossible and (sort of) succeeded. And isn’t that one of the paths to happiness?

Of course, in using animal hair, we’re doing what the Victorians would have done: practicing with something else before using the precious lock of a beloved relative. In fact, I have to remind myself that while this might seem like a craft workshop, the skill we’re learning was devised to turn a human relic—hair—into a treasured memento.

At this point, Bachman becomes reflective. “When we lose someone, we miss their physical presence,” she says. “The wearing of their hair is like keeping them with us.”

It’s a compelling idea. Whether it’s hairwork brooches or today’s equivalent (ashes turned into diamond rings or incorporated into glass paperweights), it seems we just can’t let go. But of what? What exactly are we after our heart has stopped beating—person or object?

It’s something I’ve asked myself many times. And while my book research led me to everything from hairwork jewelry to a Balinese cremation and a Czech chapel decorated with thousands of human bones, it’s a question for which I have yet to find an answer.

Quite courageous! Let me know if you do find an answer to your last question, and in the meantime, we can all admire hair as the only pieces of our earthly body that can remain unaltered by time after we die